The Forward Roll: Avoiding Option Exercise Indefinitely

Summary:

Rolling forward — replacing a current short option with another expiring later — is an attractive policy. It produces additional income while enabling the option writer to avoid or defer exercise. If the roll also replaces a current strike with a higher one (for a short call) or a lower one (for a put) the strategy also increases potential capital gains in the event of future exercise.

Click here to learn how to utilize Bollinger Bands with a quantified, structured approach to increase your trading edges and secure greater gains with Trading with Bollinger Bands® – A Quantified Guide.

However, rolling also can work as a trap in two ways. First, if a loss is created in the original position and not recaptured by the subsequent option position, then writing short options will not be profitable. Second, the forward roll in a covered call strategy can result in an unintended exercise and resulting short-term capital gain instead of an expected and lower-rate long-term capital gain.

Definitions:

A forward roll is the closing of a short option (by way of a closing purchase order) with a later-expiring replacement option on the same underlying stock. A forward and up roll refers to replacing a short call with a later-expiring option with a higher strike. A forward and down roll refers to replacing a short put with a later-expiring option with a lower strike.

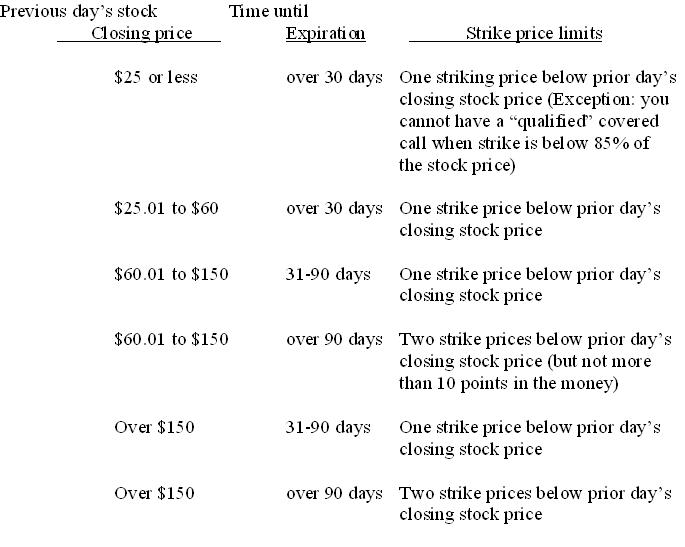

Tax consequences can apply in the process of rolling a covered call. A qualified covered call is one that resides within one increment of strike below the current value of the underlying stock, with varying levels based of qualification depending on the strike level and the time to expiration. An unqualified covered call is one deep in the money and beyond the specified qualification levels. Writing an unqualified covered call tolls the period counting toward long-term capital gains treatment of profits when stock is sold or called away.

Rules:

Rolling forward to avoid exercise is a strategy that should be considered, remembering that doing so extends the time a short position remains open. This also extends risk exposure, so the strategy has to include a comparison of potential savings with the exposure of risk. Option writers can unintentionally find themselves doing all they can to avoid exercise, even accepting a loss; this is a mistake. Exercise is one of several possible outcomes, and it only makes sense to short options if that outcome is acceptable within individual risk tolerance.

Before entering into any forward rolling strategies, especially for covered call positions, traders should understand the rules for qualified covered calls; they will want to avoid losing or tolling the count to long-term capital gains status to avoid offsetting option-based profits with higher tax liabilities.

The strategic value of the forward roll

Rolling forward involves a buy-to-close trade on a current short option, replaced with the sale of a later-expiring option on the same underlying stock. The strategy can be used for either calls or puts. The intention is to avoid or delay exercise when the option has gone in the money or threatens to before expiration.

In theory, a writer can roll forward indefinitely, avoiding exercise until the short option remains out of the money at expiration. This strategy is especially attractive for covered call writing, because the market risk in the short position is minimal compared to uncovered call or put writes. Secondly, the forward roll at the same strike produces additional income because a later-expiring option is always more valuable than an earlier-expiring option. This is due to the nature of time value, which is higher for longer expiration terms.

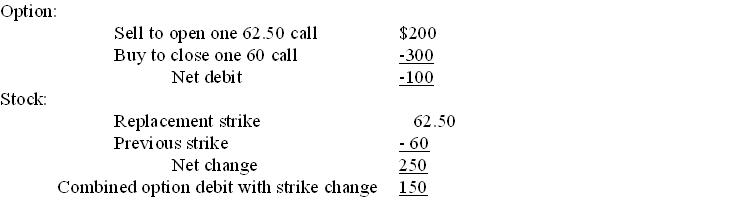

For call writes, a variation on the strategy is to replace the current short position with a later-expiring, higher-strike call. This may involves a smaller credit or even a debit. Call writers assess the value of the higher strike roll by comparing the net cost to the additional strike value. For example, if a covered call writer replaces a 60-covered call now worth three ($300) with a 62.50 covered expiring 2-months later and pays two ($200) net of all trading costs, the net effect is a $150 debit:

This means that if and when the newly rolled call is exercised, the added cost of $100 will be offset by the higher strike worth $250 more. In that event, the roll will yield an additional net profit of $150, versus allowing the previous option to be exercised.

The problem with the strategy involving creation of a debit for a higher strike is that it creates a net loss in the original short call — in this example, a $100 net loss. If the subsequent covered call is not exercised but ends up getting replaced, the loss could become permanent. For example, if the writer decides to c lose out the 62.50 covered call after it declines in value, is there any profit? Assume the newly rolled call, which yielded $200 when it was sold, declines in value to $75. This is a profit on the transaction of $125. But in truth, it is only a $25 profit; the debit created upon rolling forward was $100, and this has to be deducted from the profit on the rolled short call.

In this case, the trader earns $25 net. But what happens if the new call declines by only $75, to a new value of $125? In that case, closing it out yields a profit of $75. But when combined with the roll debit of $100, it is actually a loss of $25.

This is an example of how covered call writers can deceive themselves through excessive use of the forward roll, and create net losses without intending to. The forward roll is a valuable strategy, but there are times when it makes more sense to roll to the same strike and gain a small profit, or simply accept exercise on the position.

The pitfalls of the forward roll

The potential for creating an unintended loss is only one of the dangers in utilizing the forward roll. Part of the assessment of any strategy should balance benefit against risk — and risk includes continued exposure in a short position. Does the potential exercise avoidance justify the added time the short option remains open?

The risk is not limited to potential exercise of a short option. Rolling forward keeps you committed in the position, meaning more capital tied up to maintain margin requirements, also translating to the potential loss of other opportunities between now and expiration of the short option. Any option writer needs to continually keep the overall net profit or loss in mind, and to analyze the current position in terms of the time element as well. Short positions benefit the most in the last two months of the option’s life, when time value is going to fall quickly. So in considering a forward roll, do you want to move the open period out later than two months? This is always possible to avoid exercise, and the further out you go, the more you are able to roll up and still create a credit. However, that always means the covered position has to remain open much longer; and this is where your judgment has to come into play.

It should always be worth the extension of risk and exercise avoidance, or rolling forward does not make sense. Many covered call writers end up forgetting that exercise should be an acceptable outcome. In fact, when properly structured, exercise is a highly profitable outcome, given that profits come from three sources (option premium, capital gains and dividends). At times, it makes the most sense to let exercise happen and then turn over the proceeds in another position.

Rolling the short put

Forward rolling also works for short puts. In this situation, you avoid exercise by replacing a current short strike with one expiring later. To increase potential profits or reduce potential losses in the event of exercise, you can roll forward and down to a lower strike. The same caveat applies to short puts as that for short calls: Make sure you evaluate the time commitment risk along with the net credit or debit of the forward roll.

Whenever you short a put, one possible outcome is exercise, meaning 100 shares will be put to you at the fixed strike. This makes sense only when you consider the net cost of buying those 100 shares is a price you think is fair. The “net” cost of 100 shares will be the strike price minus what you receive for selling the put. For example, if you sell a 30 put and get a premium of 2, your exercise basis would be $28 per share (30 – 2). So as long as the stock price remains at or above the net exercise basis of $28, you will not have a net loss.

Forward rolling of puts makes sense if and when the stocks’ price falls below the net if-exercised basis. However, you still want to avoid the forward and down roll if the cost is going to represent added expense and an unacceptably longer time the short position has to stay open.

Possible tax consequences: Unqualified covered calls

A final risk involved with rolling covered calls forward involves the complexity of federal tax law. Under the rules, if you write an “unqualified” covered call before you have held stock for a full year, the count to long-term capital gains status stops and will not begin again until the position has been closed. If closing the position includes exercise, then the capital gain will be short-term, even if the overall holding period is longer than one year.

For example, if you bought stock nine months ago, you have only three months to go before any gains will be long-term. At this point, you have a 20-point gain on the stock, and you decide to write a deep in-the-money covered call. You reason that if the call is exercised, you get a nice overall profit; and that if the stock’s value falls, you gain downside protection from the call. But there is a problem. Exercise will create a short-term gain in the stock because the covered call was unqualified. For example, you might decide to write a five-month call believing that exercise at any time after another three months creates an automatic long-term gain on the stock. But if the call is unqualified, this is not the case. The profit will be taxed as a short-term gain.

This problem could turn up in an invisible way, involving the forward roll. For example, you originally sold a covered call on your $22 stock with a strike of 22.50 and expiration in 40 days. However, the stock’s price then rose to $28 per share. To delay exercise, you buy to close the original 22.50 call and replace it with another 22.50 call expiring four months later.

In this example, you replacing an qualified covered call with an unqualified one, meaning the count for long-term treatment stops as soon as the roll takes place. The rule for identifying qualified cove red calls is complex, and is summarized in the chart:

The point to remember is this: Keep the forward roll in your arsenal of strategies to manage short option positions, but always be aware of the risks: Tying up capital longer than you want, creating net losses, and losing long-term capital gains status. Make all trading and investing decisions only after you have made sure that you appreciate and know about all market, margin, and tax risks involved.

Michael C. Thomsett is author of over 70 books in the areas of real estate, stock market investment, and business management. His latest book is The Options Trading Body of Knowledge: The Definitive Source for Information About the Options Industry. Thomsett’s other best-selling books have sold over one million copies in total. These are Getting Started in Options, The Mathematics of Investing, and Getting Started in Real Estate Investing (John Wiley & Sons), Builders Guide to Accounting (Craftsman), How to Buy a House, Condo or Co-Op (Consumer Reports Books), and Little Black Book of Business Meetings (Amacom). For more info visit Thomsett’s website at MichaelThomsett.com. He lives in Nashville, Tennessee and writes full-time.