Vertical Credit Spreads

Selling a naked at-the-money option is a very risky strategy. And the purchase of an out-of-the-money option is costly, with a poor probability of success. Combine these two high-risk strategies, however, and you form a credit spread – one of the safest and most successful strategies there is.

A vertical credit spread is constructed by buying one option and selling another option of the same type (call or put) in the same expiration month, where the option sold is more expensive than the option bought, resulting in a net credit to your trading account.

In contrast to a debit spread, where you simply pay the difference between the premiums of the two options, with a credit spread there is a margin requirement based on the difference in the strike prices. For example, consider the following two call options:

Buying the 30’s and selling the 35’s would form a call debit spread, and you would pay the difference ($2.50, or $250 per unit). However, if you buy the 35’s and sell the 30’s you would form a call credit spread and immediately receive the difference (the same $2.50, or $250 per unit) credited to your account.

At the same time, you would be required to put up the difference between the strike prices (5, or $500 per unit). Note that the $250 credit you receive counts towards offsetting the margin requirement, so that the net amount you capital you have to provide in your account is just $250 per unit.

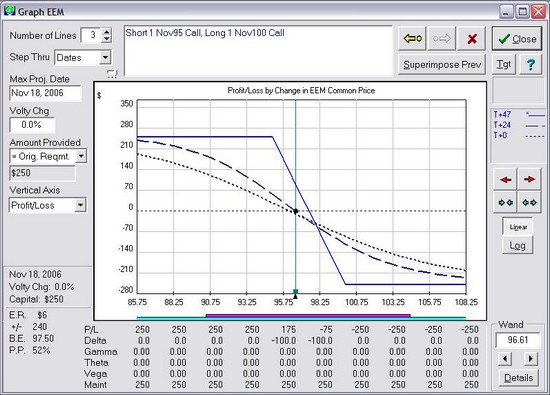

Below is an example showing what the risk graph for this trade looks like:

As long as the stock price is below $95 by the expiration date, both options will expire worthless and you get to keep the $250 credit. If you are wrong, and the stock price instead increases substantially, your maximum loss is capped at $250 – the difference between the strike prices of the two options ($500) minus the $250 credit you received.

Now you can see why a brokerage firm makes you hold margin for this trade. They want to be certain that you have the funds to settle if the trade goes against you. By requiring margin, the $500 needed for the worst possible outcome is already in your account.

Note that when you place a call credit spread, your price expectation is completely opposite that for a call debit spread. In the call debit spread, you want the stock price to go up. This would widen the spread, allowing you to sell it later for a profit. But with a call credit spread, you want the stock price to go down (or at least stay below the strike price of the call you sold by expiration). This would narrow the spread, allowing you to close it later for a profit.

If this seems a difficult concept to grasp, perhaps this will help: You can think of opening a debit spread as going ‘long’ the spread; and opening a credit spread as going ‘short’ the spread. When you go long a stock or spread, you hope it’s value increases. And when you short a stock or spread, you hope its value decreases (so you can buy it back later at a lower price).

Debit and credit spreads can be formed using puts as well, with their performance curves mirror imaging those of call debit and credit spreads. The following table summarizes:

Practically, there is little difference between the way debit spreads and credit spreads perform. Both have upper and lower boundaries to their potential values. Their value can go to a minimum of zero or to a maximum of the difference in strike prices.

Neither is there much difference in what they cost nor any practical difference in how you trade them. So when would one want to use a credit spread instead of a debit spread?

There is one distinction, and it is a subtle one. Depending on the strikes chosen, the credit spread is more often used when you have a conviction of what the stock price will not do (i.e. will not penetrate a support or resistance level). In contrast, the debit spread is used more often when you have a conviction of what the stock price will do (i.e. will continue its trend).

When there is a support level you feel the stock price will not fall below, you would typically select a put credit spread where the short option is at, or just below, the support level. If there is a resistance level you feel the stock price will not penetrate, you would select a call credit spread where the short option is at or just above the resistance level.

Sometimes the use of credit spreads is motivated more by the desire to sell options while avoiding naked writing. When a trader wants to sell out-of-the-money options to collect time premium (perhaps selling both out-of-the-money calls and out-of-the-money puts), he often buys farther out-of-the-money options at the same time in order to ‘cover’ his short options and avoid naked writing (either because of the open-ended risk of naked writing or because of its high margin requirements). This creates credit spreads.

Just as if he used naked options, the investor is expecting that the underlying will not go as far as the strike price of the short options. If he is successful, the short options, as well as the farther out-of-the-money long options will expire worthless. Naturally, his proceeds are less for having bought the farther out-of-the-money options for protection.

Len Yates is the President and founder of OptionVue Systems International and has earned worldwide recognition for his groundbreaking work in options analysis software. He has published numerous books and articles on options analysis and trading strategies, and is a primary contributor for the educational site DiscoverOptions.com.